One of the first photosets I’ve posted comes from a few days I spent in Dashoguz (in Turkmenistan) and Karakalpakstan (in Uzbekistan). Both have been dismissed by some travel writers as horrible, dreary and depressing, which to me is disingenuous. I thought I’d provide some more thoughts that I couldn’t fit into the captions.

Dashoguz District

I reached Dashoguz through the north-south road from Ashgabat, through the Karakum desert. Ashgabat’s immaculate roads disintegrate quickly as you exit the city, turning into a rutted mess. The Karakum, which Lord Curzon said was ‘the sorriest waste that ever met the human eye’, gave me this view: a full double rainbow at sunset. It seems he visited at the wrong time.

The Karakum Desert

Konye-Urgench

Getting closer to Konye-Urgench, the ground started to turn whiter and whiter - solid salt caked onto the surface, caused by poor drainage of irrigated water.

I wandered around the old site of Konye-Urgench, on the edge of the modern town. Only a handful of old buildings, from various eras, remain, on account of the city's razing by the Arabs (who, as the great polymath Biruni regretfully said, destroyed of some of the best libraries in the world), the Mongols (who massacred the inhabitants, and flooded the city), and Tamerlane (who destroyed the area’s irrigation systems). Most of the remaining buildings date to the post-Mongol conquest, when the Golden Horde governors rehabilitated the city through trade.

The sites at Konye-Urgench are in a greater state of disrepair than most of the sites in Iran and Uzbekistan. The crevices in the grand Turabek Khanum mausoleum are filled with pigeon nests, and most of the outer dome is cracked open, giving you an idea as to the double-dome construction employed across the Islamic world (and, famously in Europe, in Brunelleschi's Duomo). And there is the curving, slanting, Kutlug Timur Minaret. Repairs to the outerwork are done by rappelling down from the top.

Konye-Urgench Town

There’s a Korean restaurant in Konye-Urgench, selling something like a Korean version of Laghman (noodle soup). There are a few Korean communities scattered around Central Asia – most notably, in Tashkent, where you can get dirt cheap quality Bibimbap – a legacy of Stalin’s forced deportations of ethnic Koreans from the Russian Far East. I spend the afternoon taking photos and kicking around a soccerball with what feels like half of the kids in the town.

The new Konye-Urgench.

Nukus

Crossing into Uzbekistan is tedious but uneventful. Genial Turkmen soldiers browse through my camera, mostly out of casual interest. I don’t have to fill out a single form on the Uzbek side.

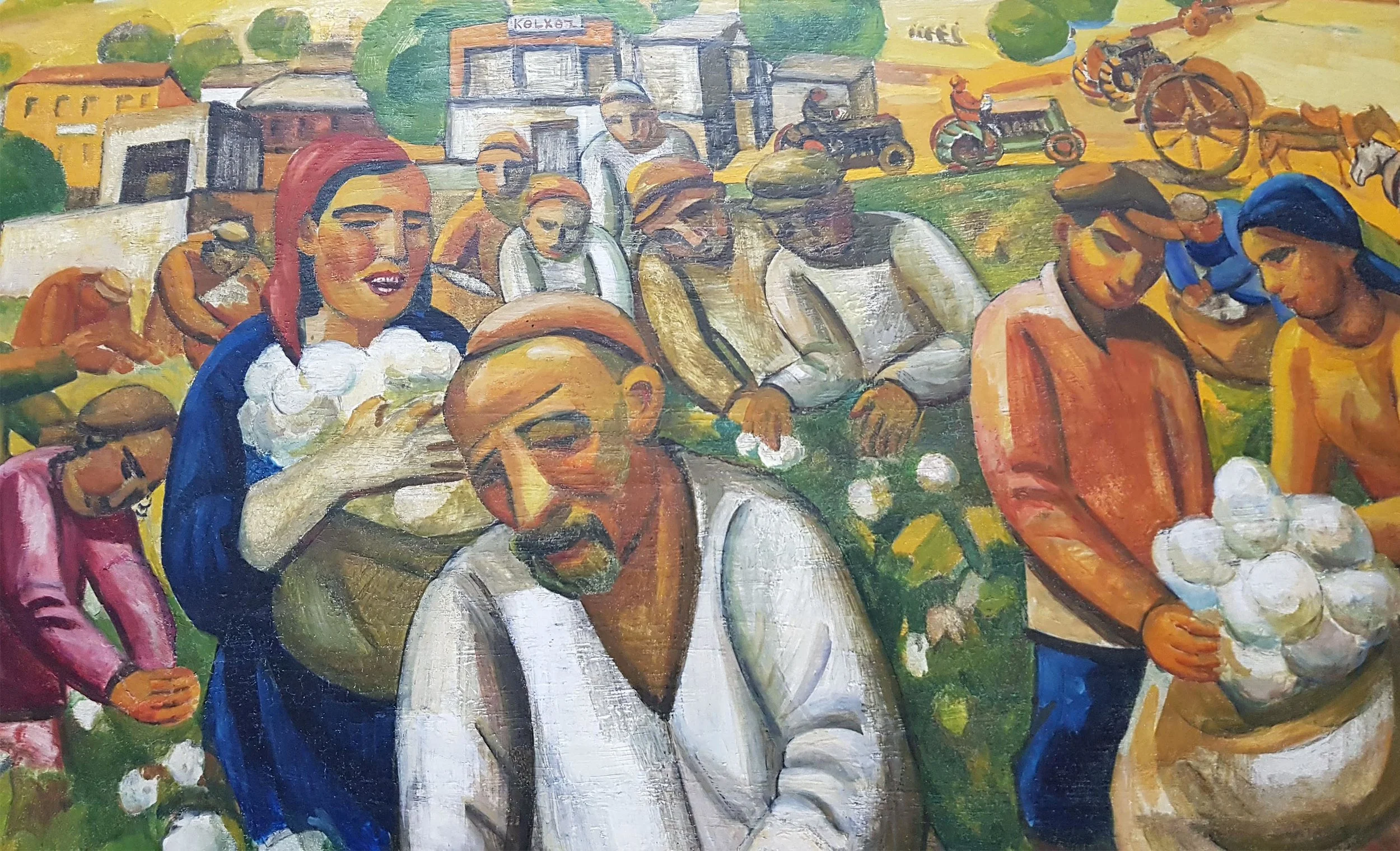

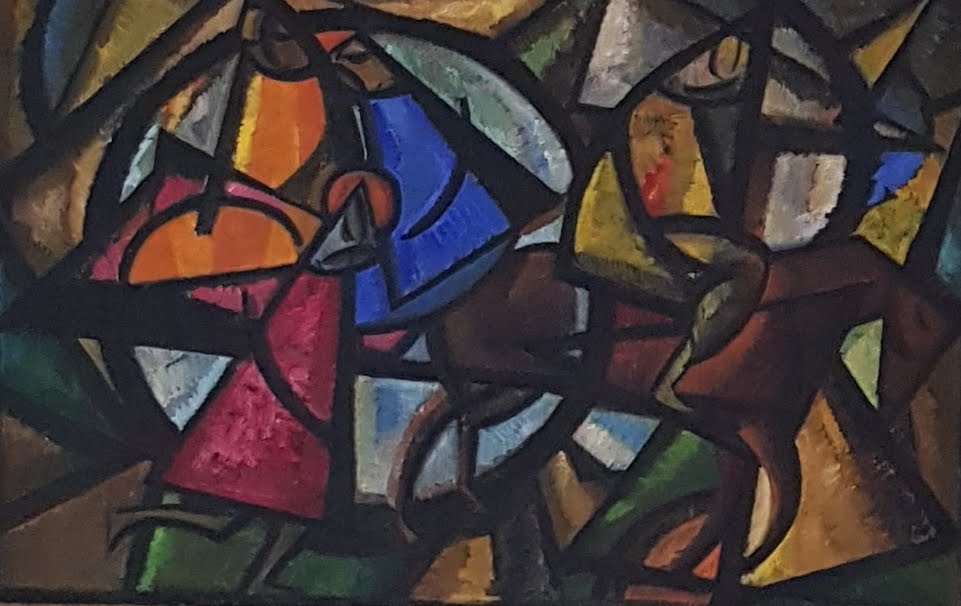

Nukus is the first major city, and capital of Karakalpakstan, on the Uzbek side. Wide, square-gridded apartment blocks dominate the centre. A thin sheen of salt covers the sidewalks. Most famously, the Savitsky Museum is here, which contains the largest collection of Soviet avant-garde art outside St Petersburg's Russian Museum. It's a remarkable museum, established by the archaeologist Igor Savitsky, who sought out the works of proscribed artists when Soviet Realism was the official art style in the USSR.

Many artists, despite being committed modernists, were surpassed by the tide of Stalinism, and many of their works were branded as counter-revolutionary.

Motifs of classical art are left behind, in one case, quite literally (Solomon Nikritin’s “The Old and the New” - pictured above, you can tell which one it is - which, out of context, is hilariously blunt, but in context, is quite sad).

A.N. Volkov’s depictions of the kolkhozes (collective farms) are filled with beaming, ruddy, farmers; another, “Cart” (above), in a faithful cubist style, is about as modern as it gets, but he nevertheless got branded as a counter-revolutionary, had his money confiscated, and was committed to living in isolation.

There is a rather cosmic portrait by Vera Pshesetskaya, who was arrested and exiled in 1930. There are the touching, soft portraits by A.V. Shevchenko, including one of a power station worker (above).

Then there is V. Lysenko’s “Facism is Advancing” or “The Bull” (above), which serves as the museum’s centrepiece. “The Bull” was branded anti-Soviet. Lysenko was arrested in 1935 and sentenced to six years in the gulag for counter-revolutionary tendencies.

There is also the famed Amu Darya, known to the Ancient Greeks as the Oxus. At this upstream location it's reduced to a small narrow canal. Given Nukus was host to the Red Army’s Chemical Research Institute, which tested chemical weapons including Novichok, I’d probably give swimming a hard pass. I spoke with a soldier inspecting a pumping station on the riverbank; we swapped watches, just for the story, I suppose.

Mizdakhan

There is also Mizdakhan, the gigantic necropolis to the west of the Amu Darya, where communist stars, orthodox crosses, and Islamic crescents sit aside each other, adorning the graves. I get there at around 7pm – the groundskeeper tells to come back tomorrow, as he has closed the place, but eventually he relents and lets me have free run of the place. The rest of the family comes along and asks I stay for the night. I couldn’t possibly impose and instead, after wandering around the necropolis until after dark, I find my way to the road and hitch a ride back to Nukus. The driver’s mother, in the back seat, gifts me a loaf of stale bread.

Not Mizdakhan, but the cemetery practically next to it. Mizdakhan is much like it.

Leaving

Another act of generosity, on another day - a baker who sees me taking photos, and pushes a loaf of bread into my hands (really, at this point I’ve been given too much bread).

Unfortunately I didn’t take the opportunity to travel north to the old shoreline of the Aral Sea. It was too expensive, and there wasn’t anyone to split the costs of a trip, so instead I turned south to Khiva, crammed into the back seat of an old Peugeot. I should've paid for two seats in the shared taxi.